The

future energy mix of this country is currently up for debate; whether we as a

country should invest money in developing renewables or commit future generations

to a legacy of nuclear waste? With strict EU laws governing the country’s

carbon dioxide output between now and 2020, at a reduction of 20% on 1990

levels, a viable solution must be found in order to keep the lights on in

British homes.

|

| Can we keep the lights on? Image @ Bes Z via Creative Commons |

In a

white paper published in January 2008, Gordon Brown, then the UK Prime

Minister, stated “nuclear power is a tried and tested technology. It has

provided the UK with secure supplies of safe, low-carbon electricity for half a

century” an opinion reiterated by the Tory Liberal coalition government in

their go ahead for nuclear regeneration in the UK and approval for ten new

reactors to be built at sites around the country, with a generating capacity of

16 gigawatts electric.

|

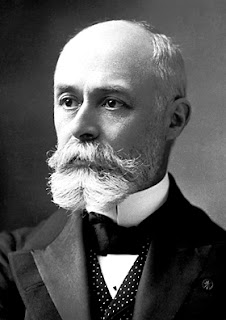

| Henri Becquerel (1903) By Nobel foundation [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

It

took American scientists six years to develop and assemble enough fissile

material to create a weapon. So confident in their creation, there was no

weapons test before the bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on

the 6th August 1945. It took almost another ten years for the first

nuclear power plant to come to fruition, realised by the Soviet Union in June

1954, their plant generated five megawatts electric.

Civil

nuclear power was pioneered in Britain at the Windscale site situated in

Cumbria, the county now home to the UK’s energy coast. The site has had a long

and varied history, starting life as a munitions factory during WWII before

being adapted in 1947 for the production of plutonium for the British nuclear

weapons programme. The first of the two Windscale Pile reactors

became operational in 1950, only three years after construction began.

|

| Calder Hall 1 Image copyright (C) The British Nuclear Group Ltd. |

Since

the 1950’s the nuclear industry has grown within the UK. The country now boasts

full fuel cycle capabilities. With the ability to convert the mined uranium ore,

enrich it and fabricate fuel all before any electricity is generated. Following

burn up in a reactor most fuel is currently reprocessed, which allows for the

reuse of fuel and better disposal of waste.

Reprocessing

is an important part of the fuel cycle and the UK boasts two reprocessing plants:

the Magnox reprocessing facility and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant

(THORP). The bulk of activities on the Sellafield and Windscale site today are

reprocessing and decommissioning of these old reactors.Throughout its sixty year history, the Sellafield site has been one of continuous building and now it is about to go into large scale decommissioning and redediation, it is set to become the largest construction site in Europe.

As nuclear technology spread to countries around the world, so did the need for regulation and agreements between nations. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was established in 1949, in response to the threat that the Soviet Union and their nuclear programme and weapons posed at the time.

As nuclear technology spread to countries around the world, so did the need for regulation and agreements between nations. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was established in 1949, in response to the threat that the Soviet Union and their nuclear programme and weapons posed at the time.

|

| Nuclear weapon test, Nervada 1957. Credit: US Government via Creative Commons |

The

UK nuclear industry has not been without its share of accidents and bad press. The seventy year history of this country’s involvement with nuclear power has

been a learning curve for the scientists working alongside the reactors and the

succession of governments footing the bill. What

started as a centrally owned branch of the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA)

has grown into a multi-billion pound legacy.

With recent changes in legislation, and the privatisation of the industry, this cheque no longer rests on the shoulders of the UK tax payer, but with the energy companies who will oversee the commissioning as well as decommissioning of their proposed reactors and the sites they occupy.

With recent changes in legislation, and the privatisation of the industry, this cheque no longer rests on the shoulders of the UK tax payer, but with the energy companies who will oversee the commissioning as well as decommissioning of their proposed reactors and the sites they occupy.

The

future of the UK and global nuclear industry is something that relies very

heavily on public opinion; governments will not support a programme that is not

favoured by the people that put them in office. This is something that becomes

very apparent after nuclear disasters like those that occurred at Chernobyl in

the Ukraine and Fukushima in Japan.

|

| Fukushima anti-nuclear protest, Tokyo Image by Courtney Stiehl via Flickr |

A similar situation arose in France, a very

pro-nuclear country prior to the incident, with over 75% of the country’s

energy generated by nuclear means, now this is set to reduce to 50% by 2025.

This

said, the UK opinion of nuclear as a source of power “remained remarkably stable

in the wake of Fukushima,” with Britons valuing energy security and the need to

reduce our reliance on oil and gas as energy sources.

|

| Sellafield Site, Cumbria Image: T. Macalister, Gaurdian, 15/02/2009. |

If

you would like to find out more about the Sellafield site or get a look inside

the heart of the British nuclear industry, the BBC documentary “Britain’sNuclear Secrets: Inside Sellafield” is worth a watch.

No comments:

Post a Comment